Three View-Changing Nonfiction Books

Strong women, forests & trees, ancient history, modern lesbians... and more!

I received so many thank yous and encouragements about my It’s All About The View post - and thank you all back in return - that I thought I’d carry the theme forward into some additional views about ‘changing one’s perspective.’ Rather than being located in any far-flung museums though, these three options are books that can be ordered via bricks & mortar booksellers and libraries, or online, from most anywhere in the world. And with each of the expanded book descriptions, you’ll find links to additional articles on related subjects.

WHY THESE THREE NONFICTION BOOKS?

Partly because they’re off the beaten tracks of the bestseller lists, but mostly because each of them, in profoundly different ways, has made me embrace new perspectives relative to those I had prior to reading. I don’t expect all of you to like them, but maybe by opening your thinking towards why I find them view-changing, that might lead you to pursue (and/or suggest!) additional works.

Firstly, each book in brief, then longer discussions follow further down.

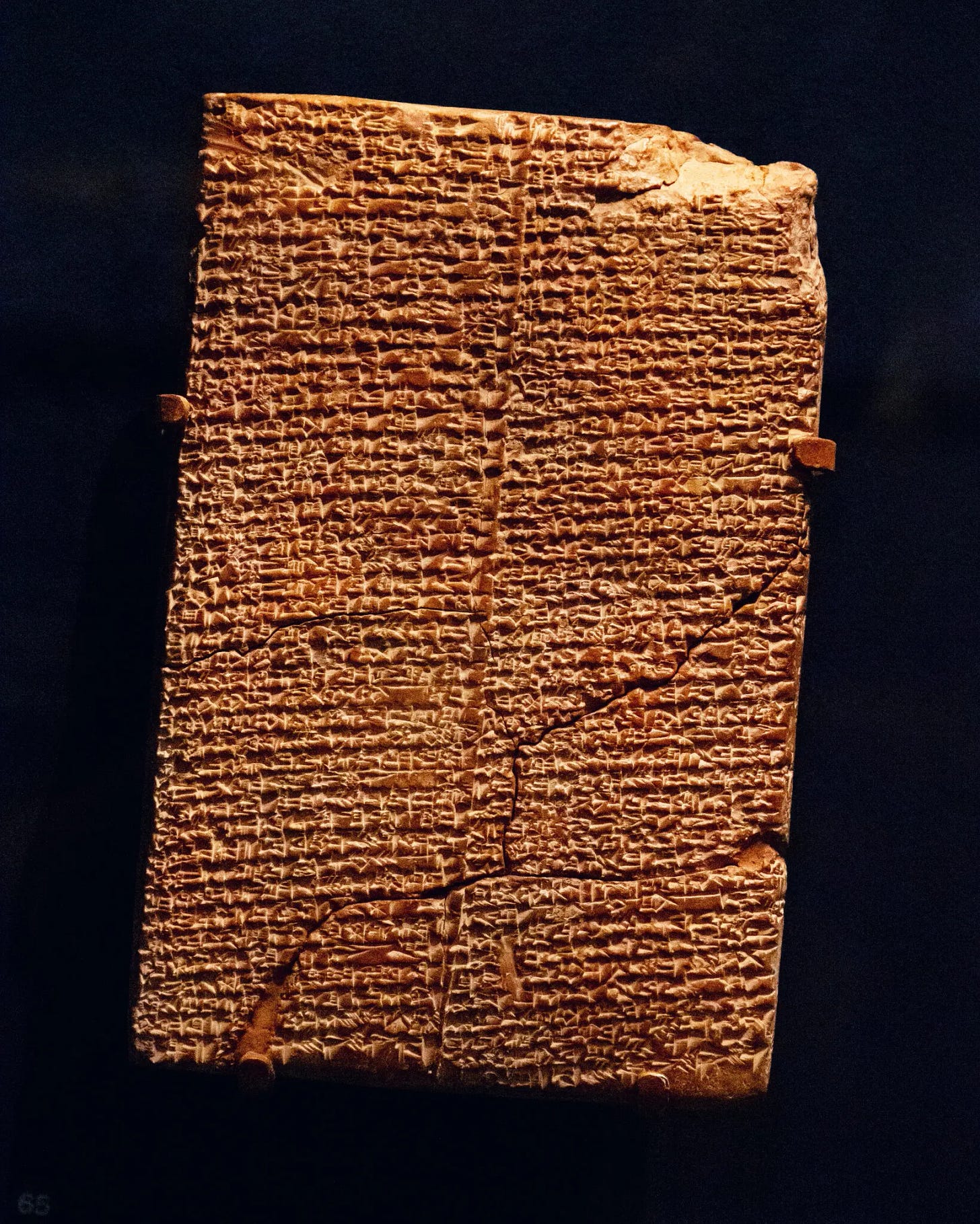

ENHEDUANA

A book of works by, and words about, the first author in the world to have texts ascribed to her name: a high priestess who lived in Ur (in what we now call southern Iraq) around 4,000 years ago. Which means roughly 1500 years before the author of such fundamental classics as The Iliad and The Odyssey. Perhaps author Sophus Helle’s words sum up this book the best:

“What would the history of Western literature look like if it began not with Homer and his war-hungry heroes but with a woman from ancient Iraq, who sang her hymns to the goddess of chaos and change?”

Not only does this book include new translations of various works attributed to Enheduana, it also opened me to new ways of thinking about history, how we translate and interpret works over time, and how much of human nature stays the same, even though we might think we evolve and change.

TO SPEAK FOR THE TREES

An intriguing amalgam of several kinds of stories. One is about a girl’s very survival and growth after losing both her parents, aged twelve. Not quite an ‘ordinary’ girl, Diana Beresford-Kroeger’s parents were both from ancient stock; her father an English aristocrat descended from earls and lords, and her mother from a pure Irish bloodline traceable to the kings of Munster. As a result, the teenage Diana receives a radical kind of immersive education. Which leads her to become an even more extraordinary kind of multi-strand professional: a medical biochemist with an illustrious scientific career, a botanist with incredible insights into the hidden life of trees, and a fierce activist for the regeneration of forests all over our planet.

But in addition to the memoir layer that informs us how these things all happened, Beresford-Kroeger also takes us by the hand and invites us into changing the world with her, simply by opening our eyes to nature and trees, by learning more about what’s available right at our fingertips, and by caring for our surroundings. In addition, a third of the book is devoted to explaining The Celtic Alphabet of Trees.

“Legend says that when a young man named Ogma created the Ogham script, nature came calling, because all imagination—even scientific imagination—originates in nature. Young Ogma looked around his neighbourhood and his eye fell on the Druids’ sacred life forms—the ancient forests.

So the alphabet of the forest was created. This new writing held the philosophy of the forest and of the millennia of oral culture that went with it. A written word is no small thing; it holds a sanctuary of thought. It is a record of renewal from the culture that originated it. With it, the Celts created the second-oldest written language of the western world.”

A CHEERLEADER’S GUIDE TO SPIRITUAL ENLIGHTENMENT

Although a departure from the ancient history threads of the previous two titles, I’ve included this one way up high on the level of ‘view-changing’. This book is an at-times hilarious, at other times tragic ‘memoir in essays’ about a young woman struggling to find her identity while growing up in late twentieth century America, as a lone girl with three brothers in a conservatively traditional, sporting and outdoorsy Italian-immigrant family, with an emotionally-unavailable father and a mother who wants her to be everything she is not. To the degree that this young girl buries her true identity for many years underneath the brittle but shiny persona of a cheerleader, until university studies and subsequent work in New York City enable her to escape and find friendship and community, romantic love as a lesbian, and success as a professional writer and activist—all on her own terms.

The author opened my view to numerous things: the Italian immigrant-American experience; a world of dedication, fierce competition and beauty standards amongst cheerleaders; what it was like to be a lesbian activist in New York, selflessly fighting for the rights of gay men who were dying in droves during the AIDS crisis years of the ‘80s & ‘90s; and somewhat unexpectedly as well, the life of a long-Covid patient, as this is a condition the author also reveals and discusses. Sadness and pain are not avoided in this book, but the author is so deft with language she manages to present them as unavoidable aspects of a life fully lived, from which one can find alternative pathways to happiness and contentment.

“Soon enough, everything my mother dislikes about me disappears under a dirt mound in the backyard, patted into the shape of a little girl who has disappeared. My mother is foolish enough to believe that the dead never come back to haunt the living.

What’s left is something brand new, an outer shell and an entity all its own.

I call this new thing “cheerleader.”

And then a bit later…

“The next time my oldest brother comes into my room at night, he’s been away at college for three years and has been out drinking.

I sit up immediately.

“Get out!” I say. He does.

I stand on top of pyramids now. My sneakers balance on the shoulders of girls who are strong and determined to win. My new place in the world is on top. My message is triumph.

I am the one who will lead us all to v-i-c-t-o-r-y.

FURTHER INTO… ENHEDUANA

I count myself fortunate to have grown up in the presence of (or been influenced by) strong women. My great grandmother Ethel Turner managed to be a highly successful author in an essentially male world. My grandmothers, aunts, sisters and nieces all were / still are strong women. And in my youth my mother, having just assisted a cow to give birth in the middle of a sodden paddock, had no qualms slipping out of her 07:00 a.m. mud-caked attire, into her 10:00 a.m. fresh-as-a-daisy tennis frock, ready to have lunch with the ladies afterwards. I find strong women cool and interesting, and simply don’t understand why, throughout history, a lot of men have a lot of problems with such women. So I enjoy a few Sophus Helle sentences like:

“Even today, female authors continue to be labeled as “women writers,” as if they were anomalies in an inherently male profession. But Enheduana’s authorship overturns that assumption: the concept of authorship began with a woman. Her hymns are a rare flash of female voice in the ancient world, and they treat themes that are as relevant today as they were four thousand years ago: exile, social disruption, the power of storytelling, gender roles, the devastation of war, and the terrifying forces of nature.”

Not only was Enheduana a princess, high priestess and author, she posited a female goddess: Inana - somewhat equatable to Ishtar - as being the most supreme deity of her time, above all the male gods. Here are some of Enheduana’s own words (as translated by Sophus Helle) from the beginning of The Exaltation of Inana:

I. Queen of all powers, downpour of daylight! Good woman wrapped in frightful light, loved by heaven and earth, holy woman of An. You hold the great gems, you love the good crown, to rule is your right: you have seized the seven powers of the gods.

II. My queen, you are the guardian of the gods’ great powers: you lift them up and grasp them in your hand, you take them in and clasp them to your breast. As if you were a basilisk, you pour poison upon the enemy, as if you wer the Storm God, grain bends before your roar. You are like a flash flood that gushes down the mountains, you are supreme in heaven and earth: You are Inana.

One of the most intriguing aspects of this book, is just trying to wrap my head around the levels of antiquity it contains. Enheduana lived around 2,300 BCE. That’s a loooooong time ago. As the author notes, “Julius Caesar lived closer in time to us than to Enheduana.” But even so, the people of her time also had myths and legends and creation stories that came from their ancient times. As friends of mine have reported after visiting Egypt, “I went there with questions, hoping to return with answers. But I’ve only come back with more questions!”

I also enjoy a device Helle employs throughout the book to clarify which ‘life’ of Enheduana he might be discussing at any given time. He borrows this from the philologist Gina Konstantopoulos; a way of ascribing to Enheduana three ‘lives.’

“In the first, she was a powerful priestess in (her father) Sargon’s empire. In the second, she was a literary star in the Babylonian schools. The third life is the one she leads now: that of an ancient poet in the modern world.”

For Babylonian scholars, Enheduana’s texts were already around 500 years old, and yet those scholars are ancient to us. It makes me wonder if we’ll ever manage to locate some kind of definitive beginning of human cultural history? And if so, what will that look like, and when will it come from?

For further reading:

She Who Wrote: Enheduanna and Women of Mesopotamia, ca. 3400–2000 B.C. - an exhibition at the Morgan Library.

Hidden women of history: Enheduanna, princess, priestess and the world’s first known author - in The Conversation.

FURTHER INTO… TO SPEAK FOR THE TREES

If you have perhaps read my Energy Flows Where Attention Goes post, you’ll know I’m an advocate for reconnecting with nature, in as many ways as we can, as soon as we can. To Speak for the Trees is definitely one of my inspirations.

I can never remember not adoring trees. They’re mystical and magical, ancient and wise, teachers and protectors. And in recent years, adoration has widened into awe, the more I discover about them, and learn that we still have SO much further to go towards understanding them. While in that same breath it becomes apparent that the more ancient forests we lose, and the more indigenous populations die out, or cease to operate in their traditional ways, the more information we’re losing about trees as well. Information that has often been preserved through oral traditions passed through countless generations. But a few things led me to this book.

The first was this mind-blowing long read published in the New York Times in 2020, called The Social Life of Forests - essentially about the discoveries of Suzanne Simard, the Canadian scientist and professor of forest ecology.

Hungry to know more, I followed that with two wonderful books by the German forester and author Peter Wohlleben. The Hidden Life of Trees: What They Feel, How They Communicate: Discoveries from a Secret World and The Heartbeat of Trees: Embracing Our Ancient Bond with Forests and Nature.

Which all led me to Diana Beresford-Kroeger’s book, To Speak for the Trees. And with this one… hey, I guess I’m just a sucker for a good story. And Beresford-Kroeger’s personal story is kinda’ jaw-droppingly amazing. She survived so many different kinds of hardships as a girl and young woman, and yet she’s managed to come through blazing, and is endlessly positive and optimistic about our ability to change the course of the climate emergency. Without just talking about it, she gets in and DOES it.

For a glimpse of this: upon the death of her mother, the older generations of her family gathered and decided that Diana would be their ‘child of destiny.’ And as a result they would give her their open secret, the gift of their ancient knowledge stretching all the way back to the Druids, while knowing that Diana would be the last to receive it in this way. So for the following ten years, Diana spent every summer in Ireland’s valley of Lisheens, learning the Gaelic language, learning all manner of practical skills - like how make different kinds of butters with various uses, learning ancient poems, songs and rhymes, learning how to work the land, and perhaps most importantly, the medicinal uses of all kinds of plants. Later in life, after becoming a spectacularly successful biochemist, time and again Beresford-Kroeger would return to her Irish teachings and discover that her ancestors possessed much of the exact same knowledge that Big Pharma is profiting from so successfully today.

And I guess I simply find Beresford-Kroeger inspiring. After marrying a Canadian, she moved to Canada, and together she and her husband have built an arboretum that stocks an extraordinary range of trees. Beresford-Kroeger has scoured the world, in search of as many kind of trees as she can find, that she believes will be the ones most capable of surviving through the climate emergency. And she’s ensuring that those species are kept safe. She’s also written the bioplan for the City of Ottawa, and served as scientific adviser on countless environmental organisations. But we don’t have to be world famous biochemists to make a difference. From the book:

“On a smaller scale, we can take on the role of guardian and steward within our own neighbourhoods and towns. (…) If you have a large tree on your street, make sure your local council knows that you value it. Every opportunity to vote is an opportunity to put someone who cares about forests in a position of greater power and authority.”

Additional references:

A delightful video interview: Teach-in with Jane Fonda and Diana Beresford-Kroeger.

Call Of The Forest – The Forgotten Wisdom Of Trees: a documentary featuring Diana Beresford-Kroeger, in which the science and enchantment of the global forest provides us with answers to modern dilemmas.

The main website for Diana Beresford-Kroeger.

FURTHER INTO… A CHEERLEADER’S GUIDE TO SPIRITUAL ENLIGHTENMENT

A person will have a hard time changing any of my views if that person is inarticulate. In the case of Mary Beth Caschetta however, there’s almost a reverse process at work. She is SO articulate, across such a broad array of topics, that I’m in danger of just tossing ALL my views right out the window! Last year, I needed to travel from Amsterdam to Hamburg and back, by train, over the space of roughly 48 hours, in order to visit a dear friend. So I spent the bulk of my travelling time reading this book; sometimes frozen in thought trying to get my head around one of the situations Caschetta had just described, at other times wiping away a tear, and then on the next page laughing out loud at yet another wonderful description, or hysterical turn of phrase. If my fellow passengers regarded me as bonkers, I didn’t care a hoot, I was having way too much fun reading, for anyone to interrupt me.

But in particular, a few things on view-changing. How about this passage for starters, after Caschetta has recently discovered that her father has written her out of her will, “for reasons known to her.”

“I find out that disinherited people are everywhere—in the news, in historical documents, literature, other people’s families—a whole silent population of the suffering and disavowed. There’s Cordelia and Jane Eyre, of course, but also real-life characters. How have I landed in such a natural sisterhood with Jane Fonda, Jamie Lee Curtis, Tori Spelling, Paris Hilton? I’m not even blond. I learn that only in America do parents routinely disinherit their children without any legal or judicial checks and balances. In most of the rest of the world, the act itself—personally, morally, legally, and culturally—is practically unimaginable. In other places, where it exists at all, it’s highly regulated by a dissuasive judicial process.”

It’s a new kind of anguish and loss that is described here because, to the author, it is so unfathomable. By sharing her experience, she makes herself vulnerable, without asking for my pity. But her bald facts trigger my compassion, which translates to me as brave writing.

But perhaps Caschetta’s biggest view-changing achievement has been alerting me to recognize the women who often go unacknowledged in the fight against AIDS - including Mary Beth herself. In various sections of the book she discusses her activism, and that of other women, both for their gay brothers who were dying in crazy numbers, and on behalf of women with HIV and AIDS, who were also desperately needing medical establishment attention.

“Every day for weeks, I fax Shalala [the Secretary of Health and Human Services under President Clinton - MC] and include different details from the lives of the lesbians who want to go to Washington to tell their stories. All of them have HIV; all have particular complaints about the healthcare system, not to mention ideas about how to fix these problems. I’m pretty clueless about how hard it is to pull off an ACT UP action and find out just how many hours, how much strategizing, and how many meetings in the community with advocates and activists it takes to make things happen.”

But eventually, she and her colleagues succeed.

““Thank you for taking this meeting,” I say. “Our goal here is to have you listen to these women today so when you create a national women’s health policy, you’ll be informed about their lives and their experience in the healthcare system.”

For the rest of the meeting, the women speak passionately about how they became HIV-infected (drug use, rape, paid sex with men), how long it’s taken them to get diagnosed (years), what their initial symptoms were (vaginal thrush, mostly) and what their experience in the healthcare system has been, especially since they were identified as lesbians with AIDS (harrowing).

I’m as moved and humbled as Donna Shalala and her coterie of civil servants seem to be. Some sit at the table with us; many more stand against the wall, seeming to listen carefully and take notes.”

I’m humbled to read of the work Caschetta and so many others did, fighting in the trenches of the AIDS epidemic.

Later in life, Caschetta finds love and marries her partner, fellow writer Meryl Cohn. I’d like to conclude this post with a delightful passage about a moment in which Mary Beth sees Meryl in a way that, apparently, alters her view.

“I sit up, pointing. “Hey!” I tell the scraggly house plants that are my only company. “There she is!” She is Meryl Cohn, a writer I’ve met on several occasions.

I’ve sat across from her—Thanksgiving, Fourth of July, New Year’s—at tables of fellow writers. Still, I’ve never actually looked at her before. Now, on TV, she exudes sex appeal and confidence. Even Oprah seems won over by her charm: green eyes, auburn hair, the cheekbones of a 1940s movie star.

During a brief Q&A, edited to one Q (Should straight people ever ask gay people if they are gay?), Meryl chats easily, explaining to the studio audience how to know when something is offensive. She offers a quick rundown of the dos and don’ts of queer etiquette. Joking about the age-old question, “What do women like in bed?” Meryl says wryly, “Other women, of course.”

Oprah, lovely and velvety, responds with a deep-throated laugh.

Further reading:

A Cheerleader's Guide to Spiritual Enlightenment: A Memoir in Essays - on Goodreads.

Mary Beth Caschetta - on Goodreads

And in case you’re interested in further readings on queer topics, you could do worse than to start here: The 25 Most Influential Works of Postwar Queer Literature (as debated in the New York Times by six opinionated writers.)

Thank you for changing my view(s) Mary Beth. Thank you for your activism, that has truly helped to change the lives of many, many people.

And thank you, and Sophus Helle, and Diana Beresford-Kroeger, for your wonderful books.

Love and light,

Matthew.

As a keen bush walker, an avid tree planter and a known "tree hugger" I must say that I was drawn into "To Speak for the Trees" ( and by no means wanting to stray from the thread of strong women, trees and modern lesbians). I love Richard Power's prize winning book " The Overstory " and was delighted to discover that Diana Beresford-Kroeger is the inspiration behind one the book's characters, woven into a narrative structure based around the life cycle of trees. I am an adamant believer in the need for modern society to reconnect to the natural world as a fundamental foundation to correcting a planet in crisis and working to preserve biodiversity of the planet's living organisms; animal, plant and microbial. The heartening learning from Diana is the need for all us to be custodians of the ancient lore of the Sacred Forest, part of the tree of life living in awe of the beauty and splendor of the natural world that surrounds us, and that the human presence in nature should be as an interconnected species not a divorced from it. On the tangent of trees I recently read Elif Shafak's wonderful novel "The Island of Missing Trees" ( highly recommended; Woman's Prize for Fiction 2022 ). Beside being deeply moved by the Romeo and Juliette themed story of love and grief set in the tumultuous modern history of Cyprus, (as you rightfully stated in your preamble human nature stays the same) , one of the most striking and sometimes polarising elements of the book is the inclusion of a fig tree as a character and voice in story, who imparts a view of the characters' past, the natural world, and the history of Cyprus. A stoic , wise and resilient narrator ; a witness to a difficult history. At first I found the voice of the tree odd but grew to love it's permanence, it's conscious connection to a history as a silent witness.

As I write this I recall dinners with my, at the time, teenage children who very rightfully expressed their exasperation of living in and inheriting the stewardship of a planet under the stresses of human induced climate change. They were challenging, heartfelt and confronting conversations. A few difficult questions that were asked of us that stick in my mind were "how could your generation let this happen ? And what did you do to or why didn't you stop it from happening? ". How let down they felt from the governance of our and previous generations was starkly evident. In my childhood I was never confronted by concept of irrevocable climate change , perhaps it was more the ravages of war and nuclear proliferation, but I was brought up to appreciate and more importantly respect the natural environment. My wife and I were candid about what we had done to consciously change our habits, carbon footprints and impacts, the environmental causes we had supported, how we had been characterised as "greenies" for expressing and showing our concerns over time, as if that was an insulting put down by more conservative thinkers. (I am proudly a so called greenie). All micro actions in the bigger, more complicated, global context of countering environmental damage. The one adage I did implore was to think of the Butterfly Effect and the necessity to Think Globally by Acting Locally; all micro actions count.

I am looking forward to doing a lot more interesting tree planting in the near future. I have always dreamt of creating my own botanical garden and building on the existing wildlife corridors for transiting koalas on the piece of reclaimed dairy farm we plan to call home. Thank you again for the bright side thought provocation.