Today I’m dipping into writings from one of my forebears: Jean Curlewis. Why? Because there’s a certain quality to her writing that manages to reach through time, and speak to what I’m attempting with these posts. So I’d like to share a few short pieces of hers. To my reading, many of the ‘bright’ images Jean presents, shine because she also references their counterpoints of darkness. After all, life at its fullest includes death. Inasmuch as a day is incomplete until it includes night, as well.

While the problems we’re facing in the world today might include <insert your choice(s) of global catastrophe here>, in the early 1920s Jean had a few to contend with as well. Australian troops suffered heavy losses during World War One, and some of those were personal to Jean. She was twenty years old when that war concluded, and its devastations penetrate into some of her writings. Then following right on the war’s heels came the Spanish Flu.

During this time Jean worked as part of the VAD (Voluntary Aid Detachment) at a Sydney hospital, assisting trained nurses who were overwhelmed by the amount of incoming patients. It was gruelling work facing the stark realities of severe illness and mortality on a daily basis. However, rather than let darkness overwhelm her (as Jean’s letters home attest), she managed to layer it through her bright, outgoing personality and keen sense of observation and, in the years ahead, produce writings that have a particular ‘edge’ about them.

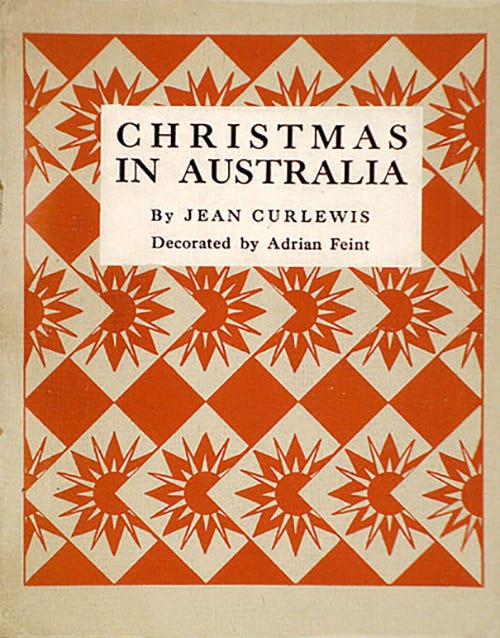

Case in point, this paragraph from Christmas in Australia, a short story published by Art in Australia as a stand-alone small booklet written by Jean, and ‘decorated’ by the eminent bookplate artist, painter and illustrator Adrian Feint.

Christmas Dawn on the beaches, the curving beaches. Beaches like flower-beds packed with moving flowers. Scarlet, jade, orange, turquoise swimming suits, sunshades, mandarin coats, like parrot-flowers on the dazzle-sanded beaches. Arrowy boys darting erect on surf boards through the foam-smother; jade-suited girls riding curly dolphins, curly sea-dragons made of tinted rubber. Out beyond the breakers, out beyond the laughter, in the surf boat, bronzed, immobile, a life-saver with a spear, a black and savage shark-spear, at his feet.

Unusual for its time, the story commences by snubbing its nose at the traditional British notion of a snowy white Christmas, then goes about depicting various Australian characters scattered across the country, going about their activities on the day. The story contains no Santa Clauses or elves or babies-in-mangers, and perhaps precisely because of this I find it refreshing. When a friend remarked upon reading it, “Wow, that’s a dark ending!” I was intrigued, because that was not my interpretation. My thought was simply, “But that IS Australia! Darkness begets light.”

As it is THAT time of year right now of course, it would be mean of me to not let you form your own opinion. So I hereby invite you to read — at whatever time and date suits you — the entire (short) story of Christmas in Australia.

(At this moment, I’d also like to apologise for the length of this particular Bright Side Writings post. I simply have a lot to say about this person / subject! You’re welcome to read now, but also feel free to return here at a later moment, perhaps for a bit of ‘holiday reading’?!)

For those who know nothing of her, please allow me to introduce you to my great aunt, who sadly, I never met. My great grandmother was the highly successful writer Ethel Turner, who retained her maiden name after marrying Herbert Curlewis, my father’s grand father. Amongst her long list of achievements, Ethel was the author of the children’s literature classic Seven Little Australians, which has never been out of print since it was first published in 1894. And in recent years, Ethel’s handwritten manuscript of this book was declared part of UNESCO’s Memory of the World register.

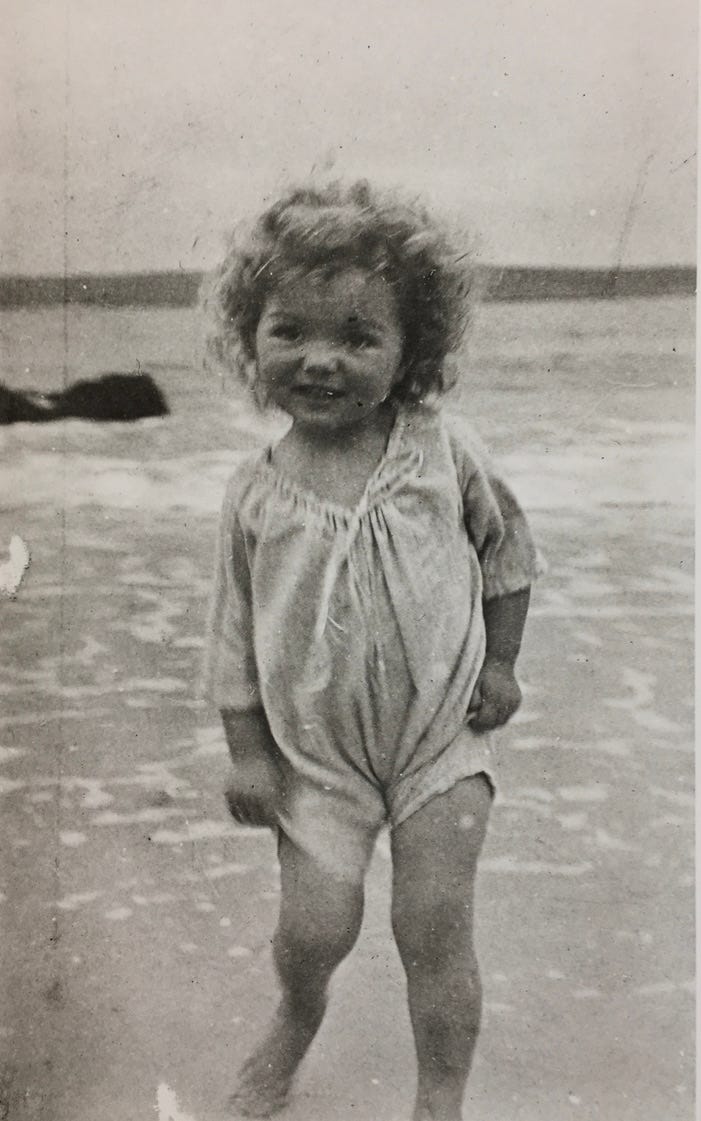

Ethel had two children – a daughter Jean, and then a son Adrian. While Adrian went on to become a judge, and the father of Ian and Philippa - my father and my aunt, Jean became a writer, and married Doctor Leonard Charlton in 1926. Their marriage appears to have been a happy one, albeit brief, and childless. In 1930, after battling through years of frequent ill health, Jean died of tuberculosis, originally perhaps contracted during her work as a VAD. She was only 32 years-old.

Growing up in the Curlewis family, I always knew about famous Ethel, but Jean’s story seemed to always disappear somehow, in the glare of Ethel’s spotlight. According to the prevailing historical record, after writing ‘only’ four novels - compared to her mother’s prodigious number of 42 - Jean died “tragically young, her career as a writer largely unfulfilled.”

That’s a pretty straighforward story, right? Nothing but sadness and disappointment to be found in THAT box in the family attic. So best steer clear of that box, yes? And stupidly, I did just that - barely glanced at it, let alone open the lid - for most of my life. Dutiful family member that I am! Until a series of ‘chance’ discoveries led me to the possibility of an entirely different story. More like the one that follows.

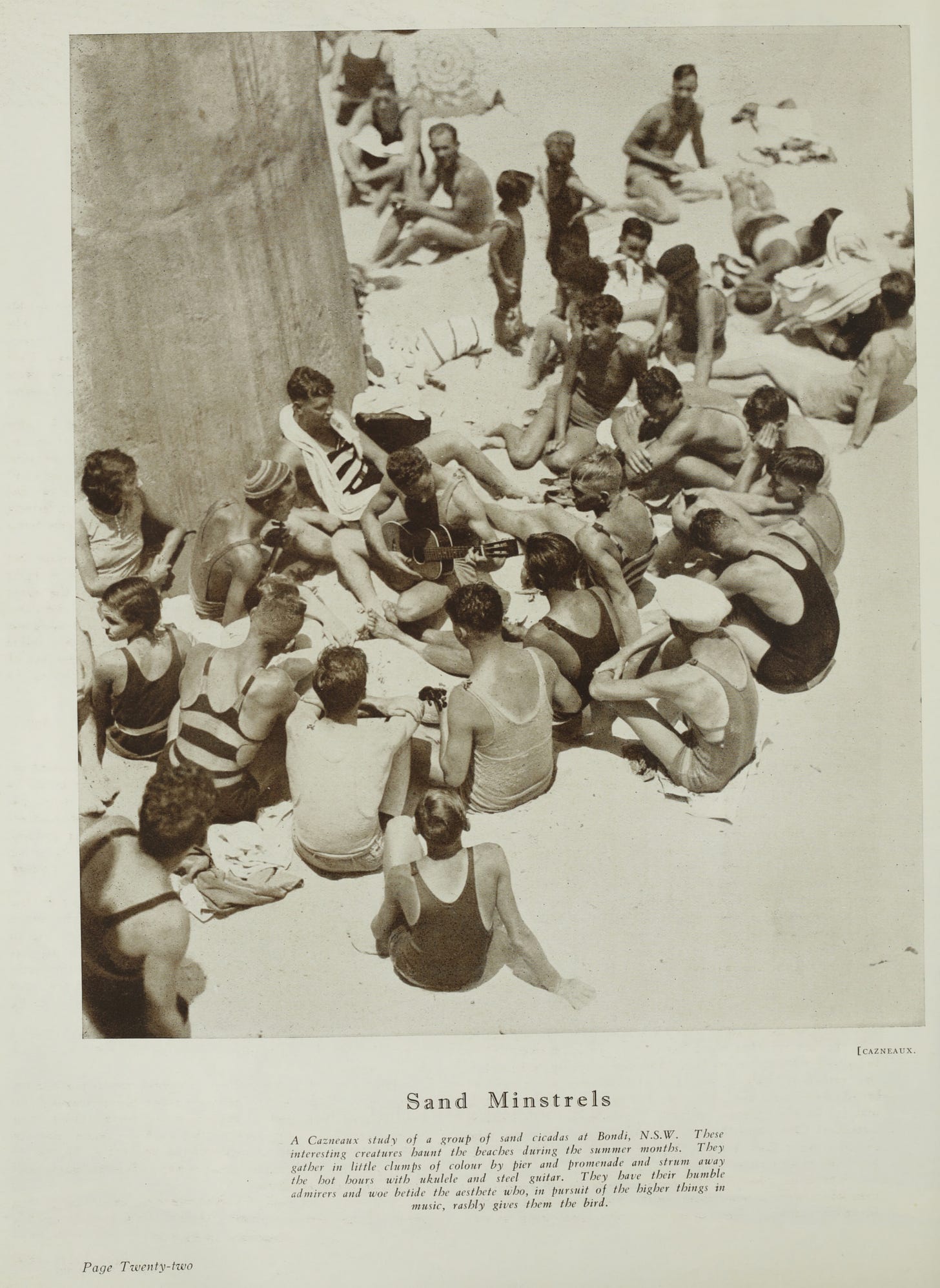

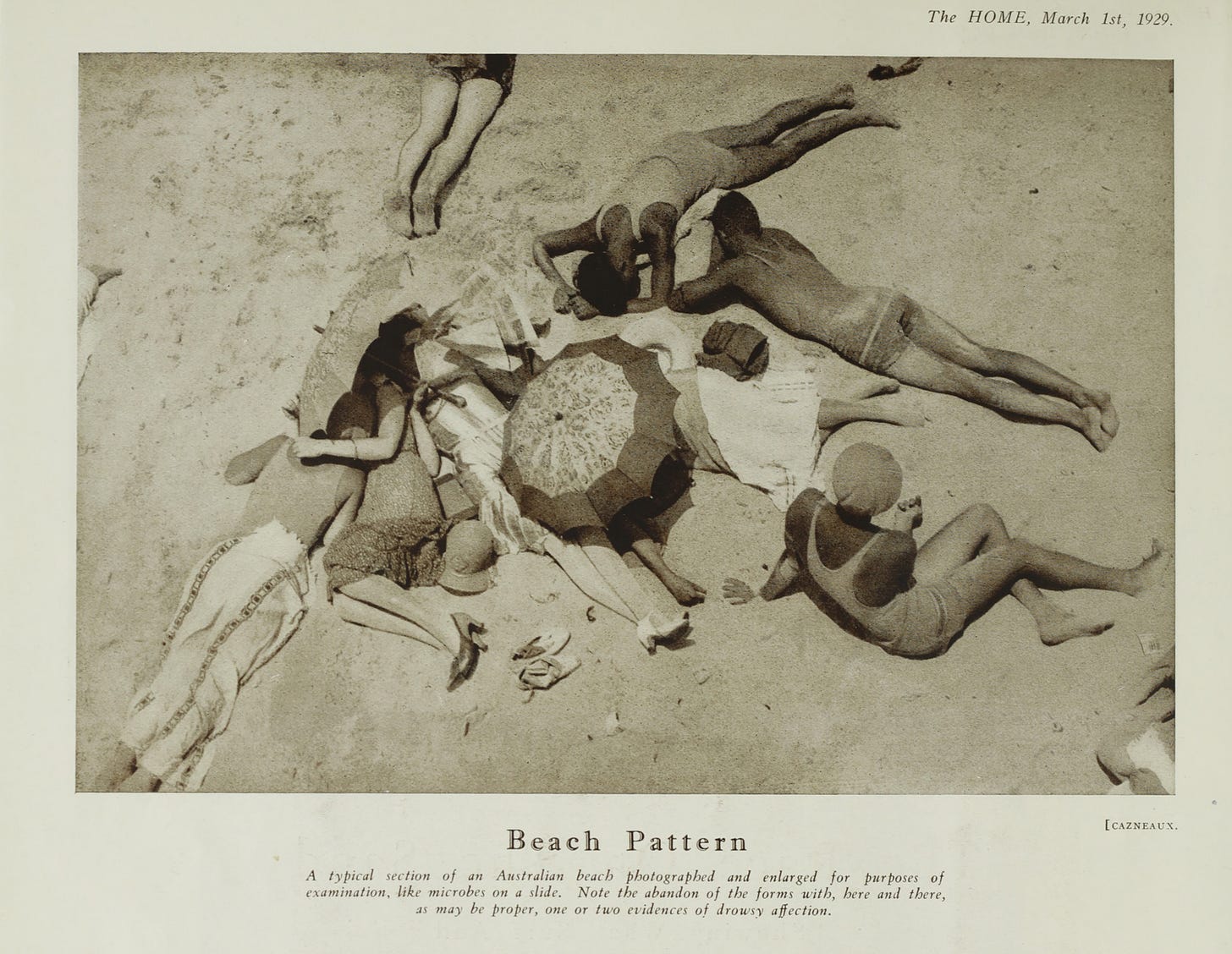

In addition to her four novels, Jean Curlewis was a hugely successful writer who was widely read, in areas extra to ‘literature’. She had columns in a variety of national newspapers and magazines. She was called upon to write numerous book reviews – not common practice at all for a woman to be writing these in the 1920s. Her poems won prizes and appeared in both national and international publications, and she authored various collaborative stories and articles with highly regarded artists from her time. These included the afore-mentioned Christmas work, and photographic collaborations such as Sydney Surfing, The Sydney Book, and Sydney Harbour, with the esteemed photographer Harold Cazneaux.

Here are two captions of Jean’s for Cazneaux photographs in Sydney Surfing:

Sand Minstrels

A Cazneaux study of a group of sand cicadas at Bondi, N.S.W. These interesting creatures haunt the beaches during the summer months. They gather in little clumps of colour by pier and promenade and strum away the hot hours with ukulele and steel guitar. They have their humble admirers and woe betide the aesthete who, in pursuit of the higher things in music, rashly gives them the bird.

Beach Pattern

A typical section of an Australian beach photographed and enlarged for purposes of examination, like microbes on a slide. Note the abandon of forms with, here and there, as may be proper, one or two evidences of drowsy affection.

Jean was a frequent contributor to The Home: the Australian Journal of Quality, the prestigious and trend-setting quarterly publication co-editored by Sydney Ure Smith and Leon Gellert. In Australia at this time, The Home was THE magazine to be associated with. According to The State Library of NSW, “The Home’s high production values, quality art paper, layout and typography distinguished it from all other Australian periodicals. It offered lavishly illustrated feature articles, full of sought-after information which encouraged cover-to-cover reading across five main subject areas: domestic architecture, interior decoration, garden design and the art of living, fashion and feminine adornment.”

Jean’s contributions run the gamut: from columns, articles and stories that artfully deal with these five main subject areas, all the way through to book reviews and profiles of, or interviews with high-profile individuals. And then occasionally Jean’s observations would be included under a group heading like the following:

With These Few Words —

A Number Of Our Contributors Conspire to Open the Month With A Paragraphic Miscellany Of News And ViewsDesolate Sundays

It is noteworthy that objections to Sunday sport or entertainments invariably come from the people who have gardens, or motor cars, wireless or tennis courts, large houses or a circle of friends, to pass the Sabbath hours for themselves. Appeals on behalf of those less fortunate in worldly belongings have fallen for so long on deaf ears that they have been practically discontinued as useless. But with this campaign to attract tourists to Australia a new argument arises. Let us not delude ourselves — tourists from the other side of the world are going to be appalled when they find themselves stranded in our cities on a Sunday.

Continental nations accustomed to combining a maximum of devotion on a Sunday morning with a maximum of gaiety in the afternoon and evening, have always shuddered at the English Sunday. But a London Sunday is a riot compared with an Australian one. For London has Sunday cinemas (those alone a big help), a bewildering richness of galleries and museums, countless cheap bus and char-a-banc excursions to the country, a number of Sunday play societies, plenty of restaurants with wide open doors and bands playing. Compare Australia.

Certainly Sydney has a Sunday afternoon harbour excursion. The steamer passes through Spit Bridge (so lures the advertisement) and tea (one shilling) may be obtained on board. But then Sydney always was given to Glittering Vice.

JEAN CURLEWIS.

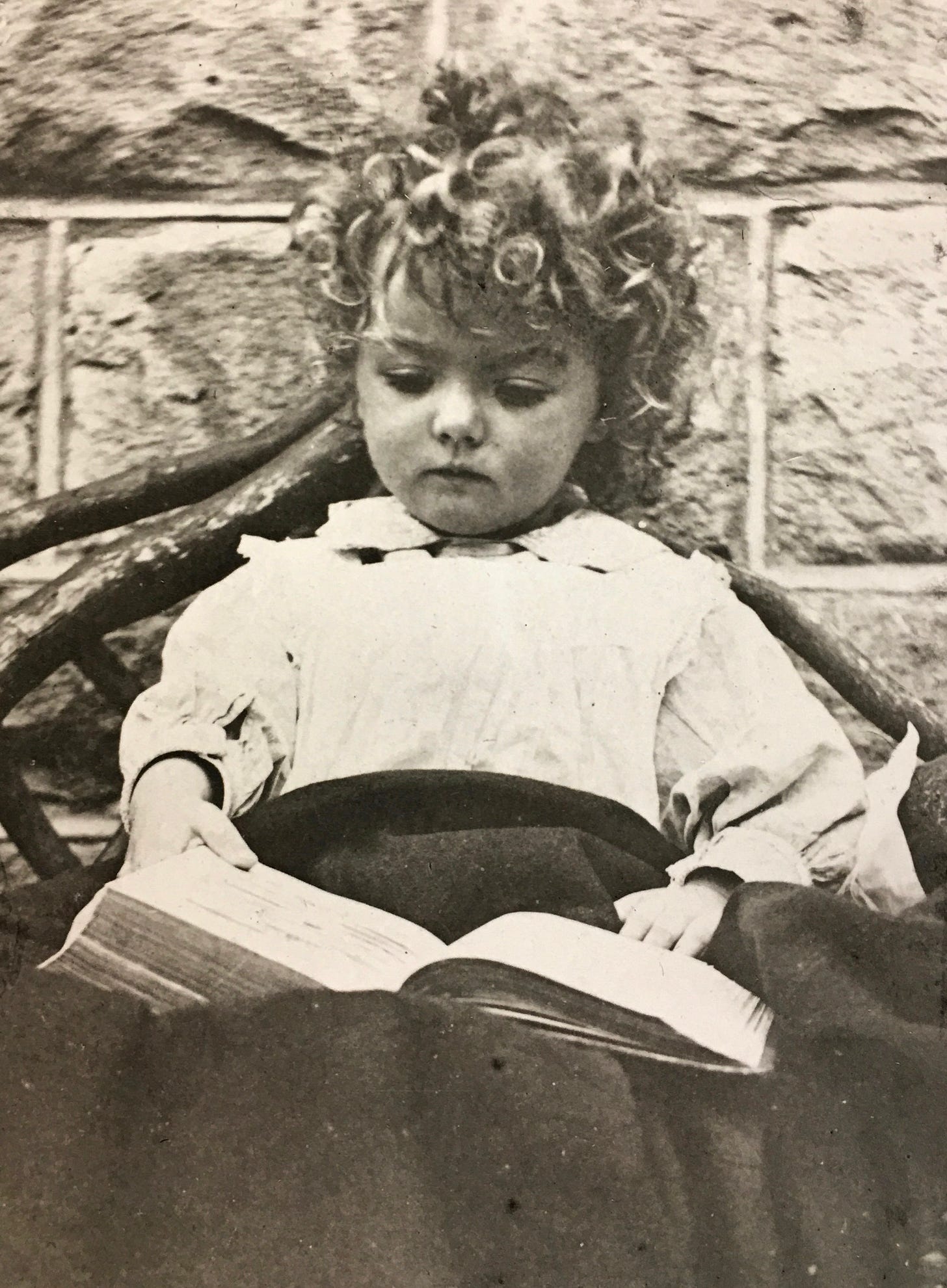

Having been a voracious reader since her earliest years, spurred on by both of her writer parents, Judge Herbert Curlewis and Ethel Turner, Jean’s book reviews in The Home gave praise where praise was due, but otherwise pulled no punches. To publish reviews as the ones that follow, it speaks volumes to me of how highly the editors valued Jean’s contributions. As a magazine, The Home was determined to lead, not to follow. And as a bright and engaged, socially-minded, internationally-conscious young woman in the 1920s, they had found a perfect fit with Jean.

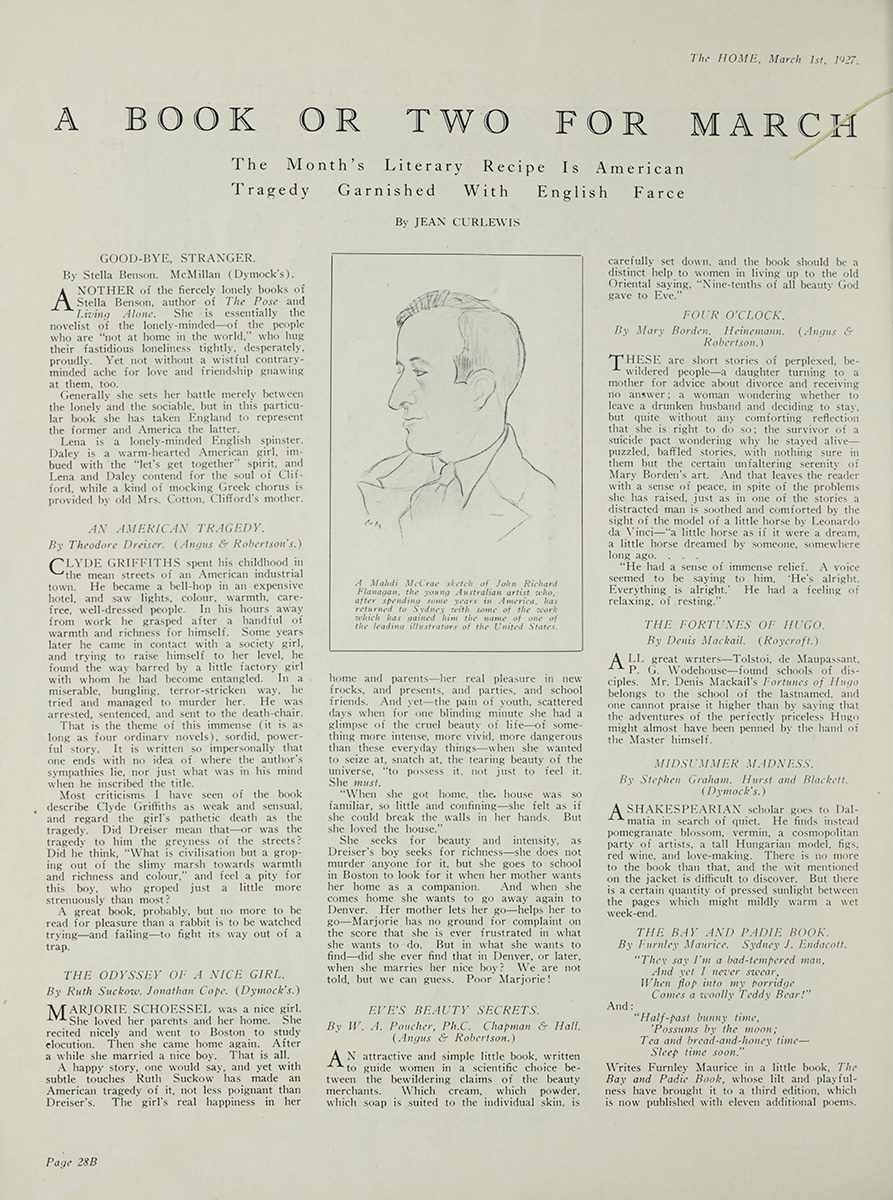

This first book title went on to form the basis of the six time Academy Award-winning, Clift/Taylor/Winters-starring, 1951 film: A Place in the Sun. I would challenge AI to come up with anything so completely original as Jean’s closing comment. Which might also explain why there is no record of Hollywood ever getting in touch to invite Jean to be a movie scout of books ‘ready for adaptation’!

AN AMERICAN TRAGEDY

By Theodore Dreiser. (Angus & Robertson’s.)

CLYDE GRIFFITHS spent his childhood in the mean streets of an American industrial town. He became a bell-hop in an expensive hotel, and saw lights, colour, warmth, care-free, well-dressed people. In his hours away from work he grasped after a handful of warmth and richness for himself. Some years later he came in contact with a society girl, and trying to raise himself to her level, he found the way barred by a little factory girl with whom he had become entangled. In a miserable, bungling, terror-stricken way, he tried and managed to murder her. He was arrested, sentenced, and sent to the death-chair.

That is the theme of this immense (it is as long as four ordinary novels), sordid, powerful story. It is written so impersonally that one ends with no idea of where the author’s sympathies lie, nor just what was in his mind when he inscribed the title.

Most criticisms I have seen of the book describe Clyde Griffiths as weak and sensual, and regard the girl’s pathetic death as the tragedy. Did Dreiser mean that —or was the tragedy to him the greyness of the streets? Did he think, “What is civilisation but a groping out of the slimy marsh towards warmth and richness and colour,” and feel a pity for this boy, who groped just a little more strenuously than most?

A great book, probably, but no more to be read for pleasure than a rabbit is to be watched trying—and failing—to fight its way out of a trap.

ONE OF THESE DAYS

By Michael Trappes Lomax.

Seeker. (Dymock’s.)

THERE are two hundred and seventy-six pages of this book. On the first page Mr. Humphrey Foyle wakes up and decides to propose to Maeve during the day. The next twenty-pages are devoted to his bath, pyjamas and dressing gown. The remaining pages deal with his efforts during the day to get that proposal uttered in spite of various interruptions. The last page puts him to bed again with it still unsaid.A quotation on the title page suggests that the author intended the book as a study in futility. He has succeeded — beyond his wildest hopes.

IT’S NOT DONE

By William C. Bullitt. Brentano’s. (Dymock’s.)The publishers advertise this as “a very modern novel.” Quite.

Shortly after their marriage, Jean and her husband Leonard departed for London where they lived during 1925 and 1926, while Leonard completed his medical studies. During these years, Jean still contributed to The Home, and maintained columns in some Australian newspapers, including the Sydney Morning Herald. Again, the editors appeared to have been broadly lenient regarding the actual content of Jean’s columns. There seemed to be a trust that, if it was coming from Jean, then it was worthy of publishing.

Going back to the beginnings of this post, I was taken aback when I first read the following. How does this writer manage to express so much brightness AND darkness so quickly, using such a tiny number of words?! It appeared in one of Jean’s ‘Lights o’ London’ columns for the Sydney Morning Herald, in 1925.

THE JUGGERNAUTS

Scene, Regent-street, between 5 and 6 this evening. A savage murderous river of traffic swirling two ways at once, instant death for any pedestrian who thinks to scud across without benefit of policeman. From the top of a bus floats suddenly a child’s balloon. We on the pavement have a glimpse of an agonised child’s face looking over the rail after it, as it settles like thistledown in the maelstrom of wheels. We shut our eyes rather than witness the moment of dissolution. When we open them again we are being treated to an exhibition of driving such as Brooklands never witnessed. Forty steering wheels have been wrenched over with a reckless hand. 40 laden two-decker buses are skidding madly sideways, lurching into gutters, putting a wheel over the kerb (what matters a pedestrian more or less), pulling up short, accelerating wildly, to clear its process as it bounds playfully about the polished macadam. A minute passes, two minutes, and still the pretty thing survives in a charmed oasis. And then a great sigh of relief goes up from us all‑-an athletic parent, who has apparently sprung from the ‘bus in full flight, comes racing back; he dives into the oasis, he grasps the balloon, he vanishes again. And in an instant the oasis is again a death-trap.

It’s getting late and I need to wrap this up, so would like to leave you with a parting image or two. Another piece Jean wrote while in London feels like it’s somewhere between an article and a short story. It was published in The Home, under the title:

LONDON CALLING!

Painting a Picadilly Night’s Entertainment as a somewhat kinematic adventure in amusement

The piece is essentially about going nightclubbing for an evening. But the descriptions and the sentiment are so vivid and engaging, that you would only have to change a detail or two to have it read equally as an assessment of going out clubbing today. When Jean’s ‘character’ finally heads home, we are left with a poignant image:

BREATHLESS and excited, we leave at last about half-past one, though the club is still in full swing. Putting on our cloaks, we glance out through the cloak-room window, which gives on to the iron fire escape. As we look the club’s French chef steps out on to it from the kitchen for a breath of air between relays of bacon and eggs. He is about fifty, tall and sturdy – the light from the window touches his rugged face, brown and droll, beneath his snowy cap. As the music throbs out to him his brown eyes light up with a charming and child-like pleasure, the spoon in his hand begins to beat time, his shoulders to jog, his feet to shuffle – a minute more and he is dancing an ecstatic pas seul.

Oh, oh! It was fun inside. Great fun. But if ever in a dreary moment I want to call up a picture of the whole joy of life concentrated into a single figure – then I shall think not of the dancers inside the club, but of you, dear Frenchman, dancing and laughing alone there on a fire escape under the stars.

Jean’s untimely death prompted moving eulogies and obituaries. Her death also proved so tragic to her mother, that Ethel put down her pen shortly after Jean’s death in 1930, and never completed another book after that date.

Included in a longer piece, Sydney Ure Smith, Jean’s editor at The Home and Art in Australia for so many years, expressed the following:

“Her work was the very essence of simplicity and she took infinite pains to eliminate everything which had no important part in the structure of her argument. I do not know of any other writer in Australia who could so simply and vividly control the presentation of her impressions of a scene or a situation. Like very few writers, she appreciated the finer things in the kindred arts, and her interest in architecture, painting, design and decoration developed her knowledge of colour and form in her own art of writing.”

Also extracted from a longer tribute, this is how the venerated author Dorothea Mackellar spoke of Jean:

She was the best kind of Australian. A young country needs enthusiasms more than an old one, and more especially does it need them to be clear-sighted, as hers were. Who can say how many lamps she lighted by what she wrote about her own land, and those others that she could appreciate and contrast with it so well? She gave us a great deal, in the short time she had.

But hey, this is Bright Side Writings. You didn’t come here to get all sad, did you?! So let’s close, instead, with the following. I’ve taken it from a letter written by Jean to her brother Adrian who was in Melbourne at the time. Consequently, he had missed Jean’s Christmas and New Year holiday period she would usually spend at the beach with friends. To describe this time to her dear brother, Jean wrote:

“Used to get up, turn on the gramophone, surf in the morning, surf in the afternoon, verandah-dance in the evening, turn off the gramophone, go to bed.”

Wherever you are this holiday season, I wish you much wonderful verandah-dancing!

Love and light,

Matthew.

I need to pay my respects and thanks to the State Library of NSW, and to the National Library of Australia. And a particular thanks to Trove, the digital collection of all resources Australian. It’s enabled me to do all my research from half a planet away, in Amsterdam!

It’s now September, 2024, and I’m making an addition to this post, which is a poem of Jean’s that in 1917, won First Prize (out of 70 entries) in a vers libre (free verse) competition staged by the national Australian publication, The Bulletin, seeking poems ‘on any aspect of the war’. Jean was 19 at the time. Here first, is the text that introduced the published results:

“The majority chose War itself—not some aspect of it. The new form is evidently not so easy as it looks. The majority of the competitors have not grasped the fact that Free Verse, despite its liberation from the strict metre of verse and the useful bridle of rime, has a rhythm of its own and demands almost the close-knitted texture of the short story or the sonnet. Thought and emotion and imagination are as necessary in Free Verse as they are in any metrical composition. Many of the vers librists merely cut their prose into arbitrary lengths and omitted all punctuation marks.”

First Prize awarded to:

SUBURBAN

by Jean Curlewis

It is eight o'clock at night,

The quiet stars are looking down into a street

of quiet suburban houses,

Behind most of the drawn blinds there is a

light shining,

It is all very quiet—

But behind every one of those windows

They know about the War.

This is a very patient people God has made:

All the day long they go about their business

And all the time they are being tortured worse

than God's Son was tortured on the Cross.

The mothers go about their daily business. . . .

You would not think when you see them at

breakfast that they have been lying awake

since the small hours, watching the light

creep in among the shadowy furniture,

Wondering

If he was killed while they were snatching a

few hours sleep—

If he suffered—

The fathers go about their daily business—

You would not think, perhaps, that they

cared very much until you meet them on

the tram and straightaway they show you

their sons' letters.

The daughters go about their daily business—

Only the sons do not go about their business—

They are not there.

The churches say that the God behind those

stars is all powerful,

All-powerful—and yet He does not stretch

out His Hand to end War !

But if God were like that I tell you that the

people would stream out of their houses

into the open and shriek until He would

have to flee away into the uttermost recess

of His heavens

So that He could not hear them.

Or, goaded into an agony of strength, they

would tear down the very battlements of

Heaven and seize Him where He sits in

His security thinking to judge the people

on Judgment Day,

And Judgment Day would be the day when

the people would judge God.

But instead there is the quiet radiance behind

blinds,

So I know that that God is not God at all.

The real God walks with them daily, helping

them—a spirit

All made up of the glory and goodness in

the hearts of the boys who were slain,

And of the tenderness in the hearts of those

that loved them,

It is after eight o'clock at night.

Clouds have blown up and blotted out the

stars,

In all the houses the War crouches menacing

and grim,

It is all very terrible. . . .

But from every one of those windows

There is a light shining.

Hi Matthew,

Another interesting one, in part for personal reasons. Jean was 2 years older than my grandfather Gavin. While she was writing for assorted publications, he was a reporter for the Sydney Morning Herald. Like Jean, he wrote reviews (for films, and art exhibitions), though also serious stuff (he reported from Germany in 1939, months before the war, and was in France as a war correspondent until weeks before Dunkirk.

He followed my grandmother to England and married her, a couple of years before Jean and her husband went to live there. When Jean died in 1930, Gavin's father (Bishop George Long), died at 50 of a heart attack, likely related to the health issues he suffered from the Spanish Flu. I could go on and on. they seem like people whose paths might've crossed in Sydney.

All the best, Adam

Thank you Matthew for another evocative and thought provoking Bright Side muse and the introduction to Jean Curlewis’ “Christmas in Australia”. I must say it resonates with me because it brings back memories of how peculiar or different my early Christmas’ in Australia were to those scribed in the story or even that of my friends. As first generation Australians, an immigrant family of “10 Pound Poms”, the Horniblow family’s Christmas was resolutely English.

From the spray on white, frosted stencils of fir trees and snowflakes adorning the windows of our house, to bob bons (crackers) and their paper crowns or table settings of candles and angels, we had all the trimmings of a traditional English Christmas. I am sure, if at all fitting, we would have even lit a log fire, eaten toasted Chestnuts and sung Christmas carols around the hearth on Christmas Eve. While the temperatures soared to the hundred degree mark and baked the paddocks to a tinder dry and crisp, golden colour, my mother would diligently crank up the stove and bake the traditional Christmas lunch . Mince pies, turkey with stuffing and rich gravy, roasted pork with crackling, or baked glazed hams, roasted potatoes and an assortment of other vegetables. A long lunch at the dining tables (yes , we joined two tables together, end on end to fit us all ) finished in a darkened room with a flaming Christmas ( plum ) pudding with the hidden lucky sixpences served with a lashing of brandy butter and whipped cream. What we were eating and celebrating in suburban Canberra was more befitting to be played out and served at a Christmas table in London or Sussex for that matter. Thankfully, while it did take us some time to become more Australian and recognise the folly of our Anglo traditions, we adapted to more seasonally appropriate norms of a hot, bright , Australian Christmas . Even going to the beach for a surf and dancing on the verandah.